Religious heritage and contemporary design

Buitenplaats Doornburgh in Maarssen was built in the 17th century as a recreational resort for well-to-do Amsterdam families. Today, the estate is a place where art and science come together in tantalizing exhibitions, workshops, and lectures. During the Vorm aan de Vecht exhibition, Doornburgh revolves around religious heritage and contemporary design. The golden FritsJurgens pivot door gives visitors access to the impressive cloisters, the design of which follows the plastic number of monk-cum-architect Van der Laan.

Historic country estate along the river Vecht

In 1623, the Amsterdam merchant Jan Claesz. Vlooswijck bought a piece of land alongside the river Vecht to build a country estate. This location – also called the Golden Bend, just like the most expensive piece of Herengracht in Amsterdam – allowed him and his family to escape the stench and heat of the explosively growing trading city in the summer. The estate would eventually grow into Buitenplaats Doornburgh, a place of great historical value. For several years, the country house and surrounding park have been on the list of national monuments.

Occupants over the years

After Vlooswijck, the estate has known many occupants, among whom were members of the patrician Huydecoper family, which produced multiple Amsterdam mayors. Many country estates did not survive the disaster year of 1672, when the Netherlands was attacked from all sides. Thanks to a generous donation from Joan Huydecoper to the Parisian authorities, Doornburgh was spared. As the three adjacent country estates – Vechtleven, Somersbergen and Elsenburg – did disappear, the garden of Doornburgh underwent some drastic changes. Originally measuring 0.85 hectares, the country estate now covers an area of over 9 hectares.

In 1684, Willem Pietersen van Zon became the owner of Doornburgh. He had the large baroque-style entrance gate built, which can still be admired in the garden. After a period of changing ownership, the country estate again came into the possession of the Huydecoper family in 1772, until 1912. In the nineteenth century, the Huydecopers commissioned garden architect J.D. Zocher to lay out an English landscape garden. Together with his son, Zocher also designed the Vondelpark. The garden of Buitenplaats Doornburgh has always maintained this original English style.

Religious twist

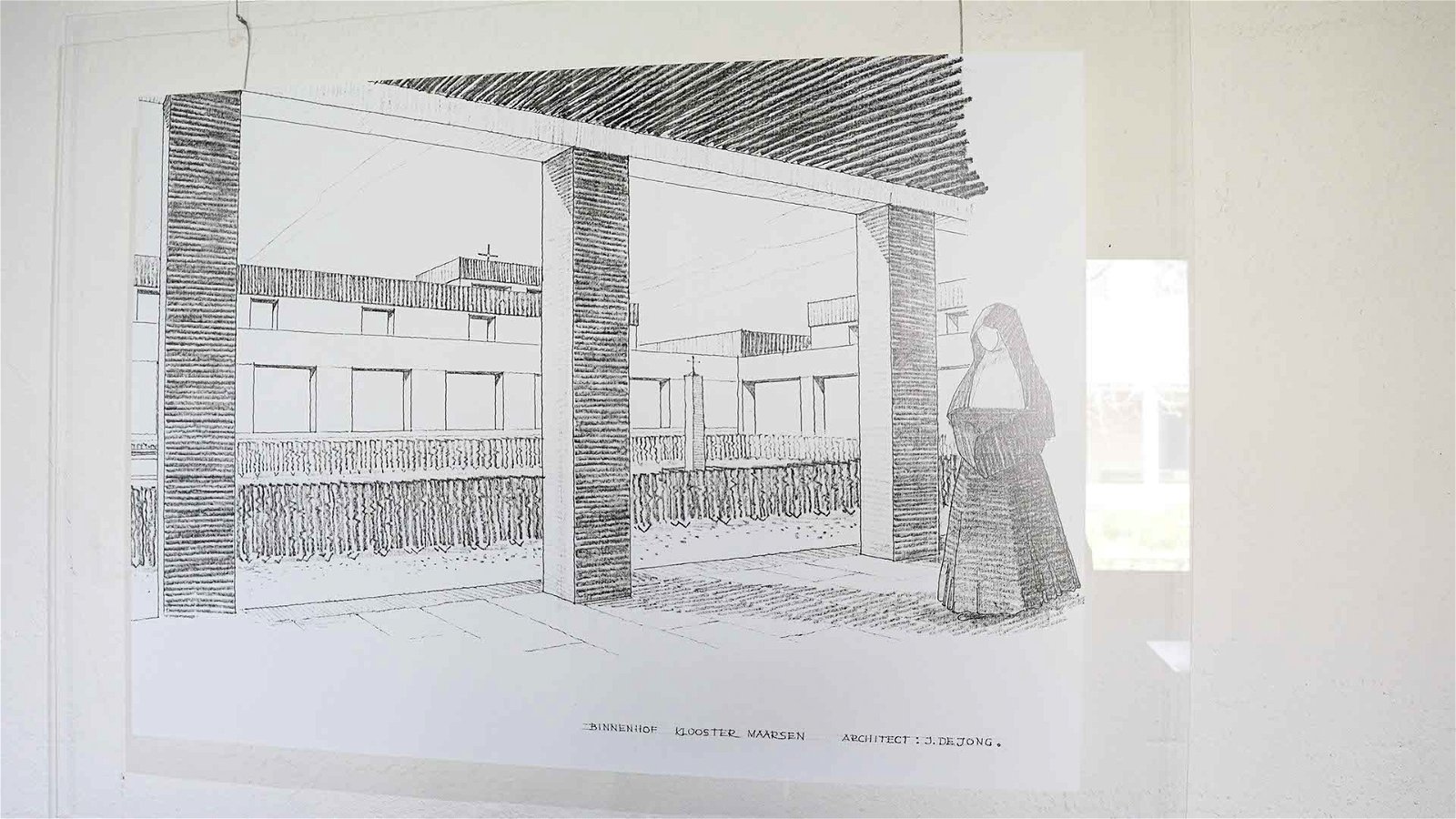

In 1957, the estate was bought by the sister order Canonesses Regular of the Holy Sepulchre, which commissioned the building of an impressive monastery complex, Emmaus priory, seven years later. The Bossche School architect Jan de Jonge designed the austere building especially for the sisters. As soon as they entered the monastery, they started their religious journey and left all their earthly belongings behind. Because the strict architectural style strongly differs from the other buildings, the monastery complex initially evoked a lot of resistance among the neighbours. Meanwhile, the appreciation for the priory has increased and, since 2016, the priory has even become a national monument. After the arrival of the sisters, the country house was used as a guesthouse.

The Bossche School

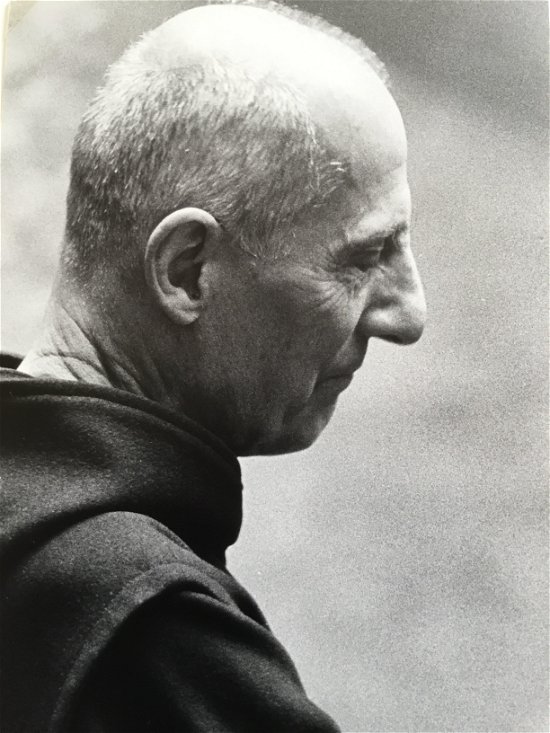

The difference between the 17th-century Doornburgh country house and the modern Emmaus priory could not have been bigger: where the former is richly decorated, the latter looks very austere. Nevertheless, the modern monastery in the Bossche School style is regarded as an architectural masterpiece. The Bossche School was founded shortly after World War II by the Benedictine monk and architect Dom Hans van der Laan. The Canonesses Regular of the Holy Sepulchre first asked Van der Laan himself to design a monastery complex. Due to lack of time – after all, he was still also a monk – he passed on the assignment to his apprentice Jan de Jong. Together, they came to the definitive design of the priory.

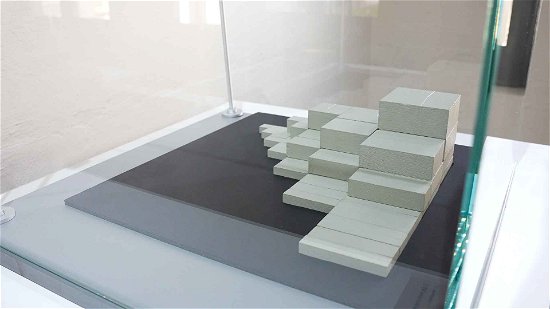

The Bossche School is characterised by strict dimensions, based on our three-dimensional perception of the world. It is all about the ideal proportions between length, width, and height, creating a space that is beneficent to both body and mind. Never before had the symmetry doctrine been implemented so strictly in a single demarcated architectural theory. Eventually, the search for perfect proportions led to Van der Laan’s definition of the ‘plastic number’.

The plastic number

According to this doctrine, a design can have no more than seven different dimensions. If there are more, people can no longer see connections, according to monk-cum-architect Van der Laan. He calculated the proportions between the different distances within a design down to the minutest detail: 1.324718. According to the Bossche School, if this number is the outcome of the formula width/length = length/height = height/(length + width), a building has the ideal proportions. Consistently applying this algebra will give every building a comforting logic.

In other words, in the Bossche School style, rooms, columns, and window frames are always in a proportion of 3:4 or 1:7 opposite each other. This is a constant reference to the divine number seven, which was regarded as sacred within the Benedictine monastery order to which Van der Laan belonged. The rules for this order were set in the year 529 by the Italian recluse Benedict. Rule number one was that the monks had to pray seven times a day. So, for Van der Laan, the number seven had a special meaning in more than one way.

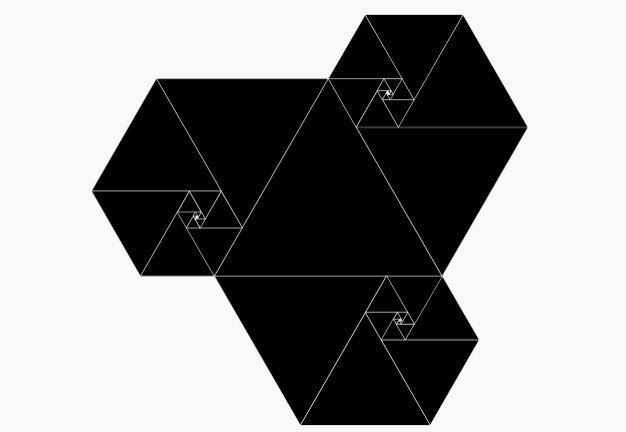

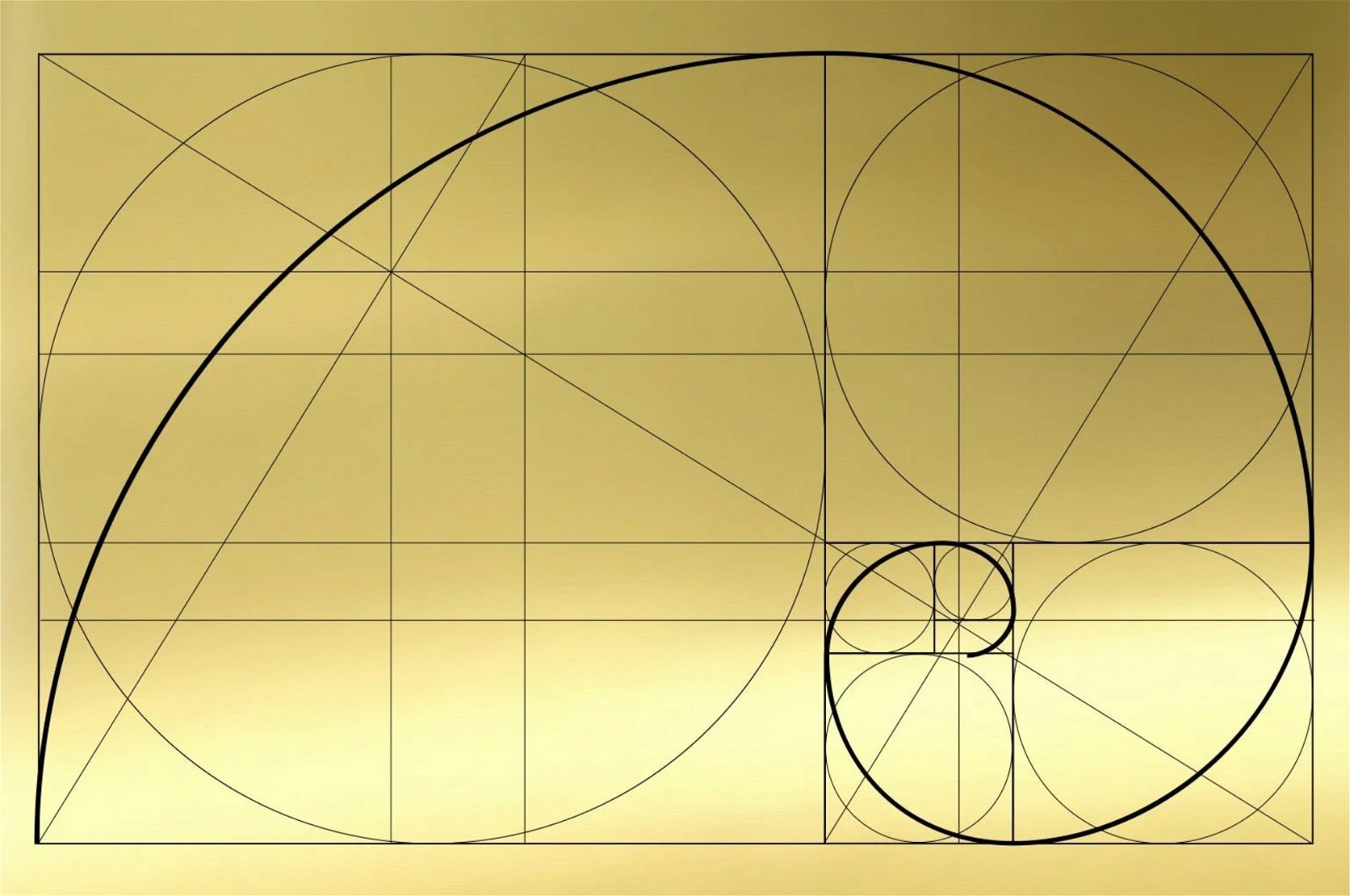

Golden section

The plastic number is derived from the golden section: a divine proportion that is often applied in, among other things, art, and architecture. You get this ‘magic number’ by dividing a line into two pieces, such that the ratio between the larger of the two pieces and the smaller is the same as that between the whole line and the larger piece. For Van der Laan, the golden section did not go far enough, because it says something about one dimension only. And architecture works with two and three-dimensional proportions. That is why he developed his own ratio, that was suitable for three-dimensional designs.

In essence, Van der Laan was not interested in the dimensions of the rooms themselves, but in what the ratio between the dimensions triggered in people. The plastic number finds its source in the way we experience the space surrounding us. The term ‘plastic’ should, therefore, be interpreted as ‘visual’ or ‘shaping’. As the monk-cum-architect himself said: “You can only see how big something is when you see it in relation to something else. You can only estimate the size of a tree if you see it in a space next to another tree.” So, the way in which elements relate to each other determines how you perceive them.

Discover more about the golden section as the basis for perfection

An eye for culture and nature

After this architectural aside, let's get back to the history of the country estate. In 2017, the last seven nuns left the priory and Doornburgh came under the management of the MeyerBergman Heritage Group, an organisation that revives historic heritage. In the past, it had been involved in the redevelopment of Soestdijk Palace and the Westergas factory area in Amsterdam.

MeyerBergman has made several changes to do even more justice to the nature at Doornburgh. For example, the lawns are mown fewer times in order to allow more stins plants – a special group of feral spring flowers that are mostly seen around country houses, castles and country estates – return. Furthermore, a local beekeeper has installed hives to enhance biodiversity. And the estate welcomed more animals: the piglets of PigMe pig farm root the meadows every year and, in collaboration with Utrecht Bird Observatory, a tawny owl box has been installed on the estate.

New function for the Emmaus priory

A restaurant named De Zusters (The Sisters) has opened its doors in the prior. The restaurant works with local suppliers and products from its own garden. What makes it special is that every course is served in a different room: the culinary adventure starts in the kitchen in the basement, proceeds in the dining hall on the ground floor, and ends in the former living room further down the building. Next to the priory is the cemetery where the Canonesses Regular are buried. Even the sisters that are still alive can be buried there if that is what they want. There are plans to build a chapel of silence near the cemetery.

.jpg)

Except as a restaurant, the former Emmaus priory is also used as an exhibition room. For example, during the Vorm aan de Vecht exhibition, work by various renowned designers, artists and photographers can be seen in a special combination of religious heritage and contemporary design. The exhibition has been compiled by Nicole Uniquole, who has been active as a curator, concept developer and exhibition maker since the 1990s. Several sisters’ cells have been transformed to rooms where artists and researchers can stay temporarily to develop and carry out projects. Throughout the year, several makers live in the former monastery as artist-in-residence to create new designs.

Gilded opening piece

The literal and figurative opening piece of Vorm aan de Vecht is the golden FritsJurgens pivot door. It seems to thwart the intentions of Van der Laan and De Jong, according to curator and journalist Jeroen Junte. “Their joint design of the priory turns its back on the earthly temptations and pompous abundance of a golden door. Unless this door is a last reminder before entering the consecrated architecture of this former nunnery.” Immediately behind the door is a massive bronze waste bin by Studio Job, where you can imaginarily leave all earthly things before entering the domain of the clergy.

From another perspective, the gilded door fits the ideas of the Bossche School perfectly, thinks Junte. “The proportions are harmonious and are consistent with the characteristic dimensions of the priory. It is almost as if the architects have assisted in the drawing of this modern door. More minimal is hardly possible: there are no door handles or frames, and the hinge has been invisibly integrated in the door. Opening the door creates an elegant choreography, the smooth movement of the door confirming and breaking the rigid composition of the stone architecture at the same time.”

Past and present

The dual role of the golden pivot door is well aligned to the aim of the exhibition, says Maya Meijer-Bergmans. She is co-owner of the MeyerBergman Heritage Group and chair of the Art Committee of Buitenplaats Doornburgh. Meijer-Bergmans: “We want to surprise visitors. By combining heritage and contemporary design in this exhibition, visitors will discover more about the past and the present.” And that is precisely one of the expertises of curator Uniquole, who is known for exhibitions where she merges different worlds in her own, unique way.

According to Uniquole, the strength of Vorm aan de Vecht lies in the combination of the historic heritage of the country estate and contemporary design. “This exhibition reflects on the special history of the country estate by putting it in a new light. We tell the story of this special location and, through the art and design shown, a surprising perspective on the future is created.”

Would you like to discover more about special pivot door projects?

Subscribe to FritsJurgens’ Monthly Featured Project and The Blog Channel and stay up to date on all pivot door trends.

Inspired by monastic life

Thanks to her experience with exhibitions at historical heritage locations, Uniquole was able to select makers who strengthen the power Doornburgh has. She took the daily rhythm of the sisters who once inhabited the priory as a guideline, as well as the regular shapes in the architecture. Uniquole: “The participating makers draw inspiration from the place. Studio Stefan Scholten made the exhibition design, based on the striking architectural principles of the monastery. In close connection with the layout and styling by Maarten Spruyt, a Gesamtkunstwerk is created.”

.jpg)

The art that can be admired during the exhibition therefore refers to the former residents and their daily lives. Both Jan Taminiau's dress with cape and the quilted long coat with hood by Moncler designer Pierpaolo Piccioli are reminiscent of nun habits. Here you find an interesting contradiction once again: where sisters wore the habits because of their reclusive and religious existence, clothes in a comparable style are now exhibited publicly.

Connection through opposites

Both the Vorm aan de Vecht exhibition and the Doornburgh country estate are characterized by a multitude of contrasts. The stark contrast between the opulent 17th-century mansion and the austere Emmaus priory is most striking, but it is certainly not the only one. Modern art in a place where nuns lived without earthly possessions, an extravagant golden pivot door in an otherwise modest building designed by the Bossche School: it is precisely because past and present seem to repel each other that they attract each other. For example, a unique collection of contemporary design breathes new life into the age-old country estate and modern makers offer us a fresh look at history.